Well, everyone else seems to be doing it, wrestling with it, whatever. Everyone seems to be attempting a definitive personal 100 of late. So, even later to the party, here's a British voice added to the mix.

For me, I think I struggled a little about 2 years ago when the moment to compile such a list suddenly hit, the opportunity to spend the necessary time constructing it arose and a momentary lapse of self-consciousness compelled me to be honest about what can often descend into a canonical parrot routine. In truth it didn't take long and I took the Schickel/Corliss route of simply noting down pictures I liked and admired, eventually whittling down that list from about 200+ to where it stands now. And there was my list. It's changed a few times in the interim and I've lost a couple of things along the way and chipped in several more.

I only let myself be led by one criteria: don't let it read like a list of perceived popular quality of the sort devised by Channel 4 viewers or readers of Empire whose frame of reference extends to few places north of 1969 and even fewer where they talk in subtitles and where Kurosawa seems the single touchstone of that foreignness worth aligning to.

God forbid 'Life Is Beautiful' is held up as a latter day example of quality either.

My relationship with these lists is touchy at best. I pour enthusiastically over Sight & Sound's bi-decadal pronouncements, often rewarded with a list by Takeshi Miike or Danny Cannon or Kim Newman that sparkles gemlike with a Darkman or a Jacob's Ladder or a Let's Scare Jessica To Death amongst the expected Bergman, Hitchcock and Renoir. But more often the popu-lists of less devout publications rile the elitist in me. Not that I'm that much of a movie fascist -- alright, there's some of that there, but since I count pictures by Anthony Hickox and Douglas Sirk amongst my personal pantheon, I guess I mostly absolve myself in the practical portion of the test. My issue is this: if you declare yourself committed enough to get to the point of qualitatively ranking films you'd better bring more than a 1st 2nd or 3rd placing at the pub film quiz to the table. Harsh, certainly. But true. To goad yourself into creating a list of any number of best pictures/songs/books indicates that you've thought enough about your love of movies/tunes/words that you feel capable of doing something so divisive and frustrating in the first place.

To illustrate my deeply pedantic and supercilious point, there's the first 10% of an Empire list from 1999 compiled by the readers of the magazine.

1. Star Wars

2. Jaws

3. The Empire Strikes Back

4. The Shawshank Redemption

5. Goodfellas

6. Pulp Fiction

7. The Godfather

8. Saving Private Ryan

9. Schindler's List

10. Titanic

(FYI: Life Is Beautiful comes in at #93.)

(FYI 2.0: 2003 yielded something better as it seemed the magazine had gained no new readers, simply the same crowd who'd simply grown up more and discovered Fight Club. A fine picture which found itself falling behind The Lord Of The Rings, now "the best picture ever made", apparently according to this new poll. I like Jackson's three pictures well enough, the whole complete entity is in my Top 100, but it's nowhere near the actual top.)

And I mean, come on. Star Wars is a picture saved by John Williams, a little imagination and buckets of youthful exuberance. It barely qualifies as a great story, let alone the greatest film ever made. It's fine, fine entertainment, but as Richard Dyer argues in a book of the same name, films are rarely "Only Entertainment" (nor are they "only intellectual exercises", "only mighty polemics" or "only subtle examinations of human behaviours". They can be all or nothing of these, but greatness doesn't rest on a single one of those virtues and nothing else).

Look, I'm a terrible reader. It's the bane of my life. I know I should read more fiction, but to my shame, the spines on those copies of Dickens, Camus and Waugh bought in a moment of committed optimism remain mostly unbroken. I am a shitty, shitty reader. And I wouldn't dream of compiling a list of what I consider my favourite books. It'd be grossly disingenuous. More than that, a total swizz. And a posturing one at that. Imagine if I supposed thus:

1. Gone With The Wind

2. Dracula

3. Harry Potter And The Goblet Of Fire

4. Captain Corelli's Mandolin

5. The Stand

6. Catcher In The Rye

7. The Firm

8. Breakfast At Tiffany's

9. something by Paulo Coelho

10. The Lord Of The Rings

Pretty strong stuff, eh? For a 12 year old maybe. (I'll say now that I've only actually read 3 1/2 of that list, probably less than many 12 years olds today have but my point still stands...shakily maybe, but stands all the same)

And the crux of my thesis here? It's not even an annoyance that someone, somewhere truly feels those 10 pictures at the peak of Empire's list are the greatest ever made. That's fine. I love that someone has 10 pictures which make them impassioned enough to declare their love for them in so public and declamatory a fashion. But you get the feeling there's not much more depth to their viewing habits if -- as in the 1999 Empire 'Best List' -- Austin Powers International Man Of Mystery and Armageddon a) appear on anyone's list of 100 best films, and b) appear atop Unforgiven, Once Upon A Time In America and Annie Hall. It just strikes me as an immensely limited sphere of interest in pictures as a 100 year old medium if they really are convinced that those titles are the 10, 25, 50 or 100 greatest pictures you've ever seen. Bravo, readers of Empire (Britain's "Best Film Magazine"), bravo.

And much as it may appear that way, this is not a snobbery against the mainstream entertainment that's laudably present on many similar, but more well-rounded lists. Jaws is a fine picture. The Empire Strikes Back is as sharp blockbuster as any I think of. The Shawshank Redemption is lovely and Pulp Fiction is formally brilliant. But I find it hard to believe anyone that loves film so much as to make a list devoted to it would not seek out the films which inspired the exceptionally cineliterate filmmakers behind these ultimately derivative modern touchstones. If they did they would find in those pictures a skill and resonance that has made them evergreen rather than simply enticing to a newly media ultrasavvy generation. How else to explain The Matrix being held up as a zenith of tricksy screenwriting and invention and Howard Hawks nowhere to be seen on the list.

There's nothing wrong with having Star Wars in your Top 10 pictures of all time either. The one list I have read which was, to all intents and purposes, most aligned to the similarly well rolling-eyeballed AFI list this past year is Roger Corman's in the 2002 Sight & Sound poll:

1. Battleship Potemkin

2. Citizen Kane

3. The Seventh Seal

4. Lawrence of Arabia

5. The Godfather

6. The Grapes of Wrath

7. Shane

8. On the Waterfront

9. Star Wars

10. The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari

There you go. Star Wars at #9. But it's sandwiched between Elia Kazan's On The Waterfront And Robert Wiene's and The Cabinet Of Dr Caligari. To me, that's an important signifier. I figure Roger Corman has contributed enough to film history to be taken at his word when declares, for him and on his terms, that these are the best pictures he's ever seen. I am in no doubt he's seen 1000s. Hell, he made as many as that. The (moderate) diversity in his selections indicates it's not just about simple spectacle. There's an appreciation of the history -- and not just the immediate gratification -- of pictures there.

Critic and writer Kim Newman (whose own -- subtitle-free, I notice, not that that's an indicator of quality -- list comprised of:

1. Apocalypse Now

2. Blue Velvet

3. A Canterbury Tale

4. Citizen Kane

5. Inferno

6. The King of Comedy

7. Let's Scare Jessica to Death

8. Notorious

9. The Shining

10. To Have and Have Not)

has said that he's not entirely trusting of anyone that doesn't have at least one oddity in their personal pantheon. I have to agree. For me, the truly diverse viewer, whether it's Jim Hoberman and Flaming Creatures or Stuart Gordon and Behind The Green Door, marks themselves out by these idiosyncrasies.

Not because they have to be different, but because I think we can all agree there's more to cinema than safe nostalgia, hulking crowd-pleasers and perceived establishment bastions. That's what got Paul Schrader and the AFI into hot water to varying degress. And it's ultimatly the sheer obviousness of many so called Best Lists that galls. Welcome newcomers to film fanaticism will probably use these scrawls as their personal compass on the cinematic journey, just as I have done in the past. You learn from those more experienced. And if there aren't honestly penned options, then how will these lists ever change? They'll pass down from film consuming generation to film downloading generation (oooh, incisive!). Some magisterial pictures really do deserve to remain lauded. Sometimes, however, the emperor has no new clothes.

So, to place my hat in the ring, the following are my 100 very favourite pictures. It's not a perfect list yet. There are a host of pictures I expect to challenge the status quo in due course. I have much Dryer and Ozu and Bresson, Altman and Ashby and Melville and Fuller still to get to on my vast 'to watch' pile. It's also in simple alpahbetical order. Yes that's a cop out. For now. Ranking it is the next arduous task. But as it stands now, this is a pretty good indicator of me -- elitist, contradictory, arrogant and hypocritical me, of course. But there you go, I'm passionate.

I want to take each film as it comes and go into what it is about it that makes it so special to me. I'm half expecting this very process to exorcise a few titles that snuck onto the list through some misguided fidelity to the perceived wisdom which I rail against above. I'll hold my hands up and shoot each one through the head with zero qualms if I have to. It's all a learning curve for me.

That 100.

A Night To Remember (1958) Dir: Roy Ward Baker

A Place In The Sun (1951) Dir: George Stevens

All That Heaven Allows (1955) Dir: Douglas Sirk

All The President's Men (1976) Dir: Alan J. Pakula

Annie Hall (1977) Dir: Woody Allen

Asphalt Jungle, The (1950) Dir: John Huston

Band Wagon, The (1953) Dir: Vincente Minnelli

Battle Royale (2002) Dir: Kinji Fukasaku

Beautiful Girls (1996) Dir: Ted Demme

Blob, The (1988) Dir: Chuck Russell

Blood Simple (1984) Dir: Joel Coen/Ethan Coen

Blow Out (1981) Dir: Brian De Palma

Blue Velvet (1986) Dir: David Lynch

Born On The 4th July (1989) Dir: Oliver Stone

Bring Me The Head Of Alfredo Garicia (1974) Dir: Sam Peckinpah

Bullet In The Head (1990) Dir: John Woo

Carlito's Way (1993) Dir: Brian De Palma

Changeling, The (1980) Dir: Peter Medak

Chinatown (1974) Dir: Roman Polanski

Citizen Kane (1941) Dir: Orsen Welles

Close Encounters Of The Third Kind (1977) Dir: Steven Spielberg

Come and See (1985) Dir Elem Klimov

Curse Of The Demon (1957) Dir: Jacques Tourneur

Dark Passage (1947) Dir: Delmer Daves

Dawn Of The Dead (1979) Dir: George A. Romero

Dead Ringers (1988) Dir: David Cronenberg

Deep Red (1975) Dir: Dario Argento

Deer Hunter, The (1978) Dir: Michael Cimino

Deliverance (1972) Dir: John Boorman

Die Hard (1988) Dir: John McTiernan

Don't Look Now (1972) Dir: Nicholas Roeg

Edward Scissorhands (1990) Dir: Tim Burton

Exorcist III, The (1990) Dir: William Peter Blatty

Fly, The (1986) Dir: David Cronenberg

Fog, The (1980) Fir: John Carpenter

French Connection, The (1971) Dir: William Friedkin

Godfather/Godfather Part II, The (1972/1974) Dir: Francis Ford Coppola

Goodfellas (1990) Dir: Martin Scorsese

Grande illusion, La (1937) Dir: Jean Renoir

Groundhog Day (1993) Dir: Harold Ramis

Halloween (1978) Dir: John Carpenter

Hannah And Her Sisters (1986) Dir: Woody Allen

Heat (1995) Dir: Michael Mann

His Girl Friday (1940) Dir: Howard Hawks

Infernal Affairs II (2003) Dir: Andrew Lau/Alan Mak

Inferno (1980) Dir: Dario Argento

Jacob's Ladder (1990) Dir: Adrian Lyne

JFK (1991) Dir: Oliver Stone

Kill Bill - The Whole Bloody Affair (2003/4) Dir: Quentin Tarantino

Killer, The (1989) Dir: John Woo

King Kong (1933) Dir: Merian C. Cooper/Ernest B. Schoedsack

Lady Eve, The (1941) Dir: Preston Sturges

Last Embrace, The (1979) Dir: Jonathan Demme

Last Picture Show, The (1971) Dir: Peter Bogdanovich

Le Cercle Rouge (1970) Dir: Jean-Pierre Melville

Le Samourai (1967) Dir: Jean-Pierre Melville

Leopard, The (1963) Dir: Luchino Visconti

Long Day Closes, The (1988) Dir: Terence Davies

Manchurian Candidate, The (1962) Dir: John Frankenheimer

Manhattan (1970) Dir: Woody Allen

Marathon Man (1976) Dir: John Schlesinger

Midnight Run (1988) Dir: Martin Brest

Mildred Pierce (1945) Dir: Michael Curtiz

Mission, The (1999) Dir: Johnnie To

Night Of The Hunter (1955) Dir: Charles Laughton

Night Of The Living Dead (1968) Dir: George A. Romero

Oldboy (2003) Dir: Park Chan wook

On The Waterfront (1954) Dir: Elia Kazan

Once Upon A Time In America (1984) Dir: Sergio Leone

Out Of The Past (1947) Dir: Jacques Tourneur

Outlaw Josey Wales, The (1976) Dir: Clint Eastwood

Overlord (1975) Dir: Stuart Cooper

Pat Garrett & Billy The Kid (1973) Dir: Sam Peckinpah

Pickup On South Street (1953) Dir: Sam Fuller

Point Blank (1967) Dir: John Boorman

Prodigal Son, The (1982) Dir: Sammo Hung

Rear Window (1954) Dir: Alfred Hitchcock

Red Shoes, The (1948) Dir: Michael Powell

Remains Of The Day, The (1993) Dir: James Ivory

Runaway Train (1985) Dir: Andrei Konchalovsky

Searchers, The (1956) Dir: John Ford

Seven Samurai, The (1954) Dir: Akira Kurosawa

Silence Of The Lambs, The (1990) Dir: Jonathan Demme

Singin' In The Rain (1952) Dir: Gene Kelly/Stanley Donen

Stand By Me (1986) Dir: Rob Reiner

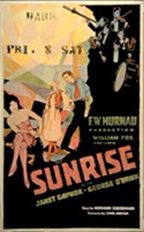

Sunrise: A Song Of Two Humans (1927) Dir: F.W. Murnau

Sunset Boulevard (1950) Dir: Billy Wilder

Suspiria (1977) Dir: Dario Argento

Tae Guk Gi (2004) Dir: Je-gyu Kang

Taxi Driver (1976) Dir: Martin Scorsese

Thing, The (1982) Dir: John Carpenter

Third Man, The (1949) Dir: Carol Reed

This Is Spinal Tap (1984) Dir: Rob Reiner

Tootsie (1982) Dir: Sydney Pollack

True Romance (1993) Dir: Tony Scott

Umberto D (1952) Dir: Vitorio De Sica

Unforgiven (1992) Dir: Clint Eastwood

Vertigo (1958) Dir: Alfred Hitchcock

Waxwork (1988) Dir: Anthony Hickox

Wild Bunch, The (1969) Dir: Sam Peckinpah

Friday, 27 July 2007

Monday, 18 June 2007

Five Great Foleys

David Fincher's newly impervious, lead-lined rep rests upon his enviable status as a visual savant. He's an idiosyncratic seer of visions (rather than an overt visionary -- he's more of a hyperbolic pragmatist than a dreamer of grand dreams a la Kubrick) eliciting images that only someone with that eye could extract and isolate from the million others pummelling their retina daily.

Finally catching (unlike his new picture's "heroes" Graysmith or SFPDs finest were able to do) the Zodiac last night, it struck me that Fincher is in possession of not only a painter's eye but a Mozart-like ear as well. The talented fucker.

I have to confess that, amid the quietly, though audaciously, staged carnage and slathering of period minutiae about the scope frame, what jazzed me most about the picture was just a simple phone call. Or should I say a raft of simple phone calls. Or perhaps I should really specify half of a raft of simple phone calls. For all the myriad, exasperatingly dense detail being exposited upon the eavesdropping viewer during countless scenes of telephonic investigation and reportage by Jake Gyllenhaal's Graysmith, Robert Downey's Avery and Mark Ruffalos' Toschi, the sound design of the person on the other end of the phone was what gave me the most pleasure for those two and half quite mesmerising hours. It's just so emblematic of Fincher's dedication to a sequence's particularity. Sure, the wide angled, deep focus newsroom and sanguine-in-the-face-of-it-all editorial meetings is a fine nod to All The President's Men. But the more tacit (or should that be simply "more subtle"?) homage to Pakula's incredible thriller was the timbre and breathy tension of those piecemeal 'deepthroat' conversations.

Call it one of those intensely personal cinephiliac moments, call it fastidious but I find myself with a need to call it. Here, amid the ebbing mood board Fincher constructs as his aural landscape, the myriad sounds of an compulsively, obsessively existence-eclipsing investigation enshroud us as much as the era's languid funk, as realised by Donovan, Gordon Lightfoot, Issac Hayes and the whole gang. He has inspired some fine co-conspirators.

Sound designer Ren Klyce has been with Fincher as a sound effects editor since Se7en (yes, "7", it's how the credits spell it -- damn the stigma of such pedantry all to hell) and Richard Hymns, also Fincher's regular sound editor since Fight Club, has a career stretching back to Lucasfilm in the 1980s and across an impressive array of Spielberg productions, riding (no doubt thunderous) shotgun alongside Gary Rydstrom and Ben Burtt and winning 3 Academy Awards and nominated for a further 4 for his toil.

That simple, clipped static effect on the end of a phone meant the difference to me, between a good picture and a great one.

Here are five more scene stealing aurals:

1. Blow Out: without a shadow of a doubt (Hitchcock allusion intended) De Palma's elegantly tragic thriller is one of my most favourite pictures (see the side bar to your right). An exploitation heart pumps the chilled blood round its celluloid story of John Travolta’s skilled b-movie soundman, Jack Terry, who toils away his days, and more often his nights, creating sounds and screams to supplant the obtuse effect of derivative visuals and vapid starlets in a host of terrible slasher films with titles like "Co-ed Frenzy”. During a routine sound scout, he witnesses what appears to be a tragic car accident. But after rescuing the sole survivor of the crash, Sally (Nancy Allen), he’s drawn into the incidents aftermath and it appears much more is afoot than mere misfortune. His inquisitive (and, it’s revealed, somewhat self-destructive) sensibilities pull Jack and his new ward Sally further into the sinister and murderous affair involving corrupt senators, sleazy snitches and a maniacal killer played with admirable salaciousness by John Lithgow.

Aside from being a rollickingly tense thriller, Blow Out is simply an unsung masterpiece of films about film. It’s a perfect distillation of every film nut's fear that eventually, as sure as day follows night, their obsession will consume their every waking thought, action and emotion. It's a portrait of the filmmaker's purgatory, deliciously grandiose, operatically tragic and hysterically funny all at the same time.

It's inconceivable that De Palma wouldn't have at least talked this idea over with Paul Schrader at some point, given he and Schrader’s collaboration on the similarly fraught tale, Obsession. It’s fortuitous then that Schrader didn't lend is scripting abilities to this project because his tautly puritanical, Protestant leanings would have stripped all the ripe hyperactive emotion with which De Palma's achingly Catholic guilt imbues his own screenplay. Horror is often emotional truth disguised as fantasy. Here, that truth, as played by Travolta, is laid bare with a raw honesty and genuine compassion quite unexpected in an essentially glossy skid row thriller. The dazzlingly controlled camera work and cutting by Vilmos Zsigmond and Paul Hirsch respectively parries with a score by Pino Donnagio that’s laced with romantic catastrophe the picture rolls, reels and eddies its way toward a punch line as mesmerising, audacious and devastating as Oldboy. In the picture's final seconds, a simple grimly ironic sound gag encapsulates one man's spiritual destruction and despair at a modern world full of bastards and liars. You’ll never think of scream queens in quite the same way again.

2. Inferno: halfway through Argento's kaleidoscopic fever-dream, Gabriel Lavia (something of a whipping boy for Argento in the late 70s -- though not quite to the extent John Morghan was for Lucio Fulci) is demonstrating his chivalrous nature, keeping neighbour Irene Miracle company as a storm ravages the electrify supply in their sumptuous and preposterously gothic New York apartment block. As Verdi churns merrily away on the funky retro turntable in an effort to calm the undulating atmosphere, the power flicks on and off at irregularly patterned intervals, the music and light dipping and ebbing away in stark unison. Through the unease of this disconcerting aural assault Lavia wanders away down a tenebrous (...sorry about that) corridor to investigate the fuse box, chirping reassuringly that Miracle has nothing to worry about while he's there. Until his voice disappears amid the staccato throng of Verdi's chorus and the apartment's faulty wiring. It's such a simple effect, but coupled with the almost impenetrable blue and red tinted gloom, it makes for one of Argento's most unsettling sequences of pure fright.

3. Come & See: there's a device in Elim Klimov shattering masterpiece which was appropriated, no doubt reverentially, by Steven Spielberg for his beach-storming précis to Saving Private Ryan (and subsequently filched by all and sundry from that blockbuster with, even less doubt, little interest in its forebears). It's partway through Klimov's picture that the central character( Florya)'s, ability to hear is blunted during the ferocious heat of battle, demonstrating the beginning of this teenager's wrenching transformation from boy to somewhere between man and lost and wretched animal.

With its impulsive, ramshackle charm and woozy innocence, the depiction of Florya's uncomprehending desertion from the WWII Byelorussia resistance movement in which he is caught up must have been an influence upon Terence Malick's later The Thin Red Line (as Badlands may well have been to Klimov, with its scenes of unnervingly incongruous youthful frivolity). Certainly the jagged disruption of the bucolic harmony (no matter how war torn the landscape in which it plays out) where Florya and his female playmate enjoy an almost magical seclusion is mirrored more than once in Mallick's quiet epic demonstrating both filmmakers' disarming power. In Come & See Florya's face becomes etched with metaphorical scars aging him to the point of abject madness. It reaches a point where he is completely disoriented as a human being, let alone as his own vulnerable self. Pulling the sound from his ears is a masterstroke of empathy, not only in generating fear at his literal and perilous geographical situation or the fog of war surrounding him but for the way it so easily elicits our instinctual desire to protect this poor boy.

It's possible Klimov may well have witnessed a similar, more experimental version of this device in Stuart Cooper's Overlord, but here, it's hypnotic and powerful to dazzlingly cumulative effect.

4. Once Upon A Time In America: lustful both in its appetite for violence and aggravated sexuality as well as being capriciously torn between a yearning remembrance of things past and wishing perhaps they had somehow been different, Leone's epic is repellent and deeply beautiful in equal measure. Which of course lends it the scope of its humanity. Goodfellas is harsh and ugly in parts but Leone's delirious and sprawling epic aims to reveal all sides of a life's journey -- not simply a series of masterfully orchestrated snapshots delineating the peaks and troughs of in life with the gangsteratti. It is flawed like its characters: repugnant, frustrating, enlightening, charming, audacious and full of the aforementioned lust.

And like the elliptical nature of memory and the narrative here, the presentation of these characters, most notably our emphatically troubled protagonist, David 'Noodles' Aronson, is lucid, perceptive, hallucinatory -- and perhaps unique ? I wouldn't suggest the resume of my picture consumption is broad enough to make that last brash claim. It's possible, though. There is no better example of this in the picture than during the opening moments, after the mellifluous longing of Morricone's theme has faded, and Noodles lies, prone in the dense fog of an opium den. The soundtrack is assaulted by a coarse ringing. It's a phone, it's an alarm, it's a warning, it's a signal, an epiphany...It's all of these things and Leone maintains its shrill intrusion for what seems like an eternity. We move from the opium den to a police incident room to a rain-swept crime scene to a dingy hideout pad, not knowing from where this clarion call emanates. More than once, we see a telephone being picked up, answered and still the ringing continues, taunting us. Noodles, whether physically in each scene, or simply aware that it must be taking place given the twists of fate that seems to have left a number of freshly charred corpses confronting him and a gaggle of onlookers on the streets of New York in one shot, is being hounded across the passage of time by this shrill tone. Over the course of the next 220 minutes we are given a sprawling (if never explicit) indication why that might be the case, of what course this man's life has taken, who he has betrayed, who has betrayed him, what he has gained and lost. Says Dana Knowles "[Leone's] transitions are visual and aural, directorial mastery ringing through them like the telephone that nags and nags at Noodles and ignites his memory in that opium den." Is there a better expression of guilt in cinema than that kaleidoscope of images and sound of the phone calling out to Noodles incessantly through the ages?

5. Singin' In The Rain: "madcap melancholy" might seem a strange assessment to level at this wonderfully vibrant musical celebration, but I'd argue passionately that it's right there. Singin' In The Rain is a film of naturally cynical dichotomies. It celebrates a time when silent film was a giddy, carefree romp that managed to uncaringly squash its mismatched and estranged screen couples uncomfortably together in ever effusive tabloid hysteria. It also explores the rush of the liberating and electrifying technological advancements that transported the industry into the sound era yet paved the way for ruthless exploitation/sacrifice of once great billboard names and their rather bitter aftertaste of post-oral fame. It's all undercurrent to a magical, elegant, pitch-perfect love-story-cum-rollicking-fantasy of course -- one of the best. It's an undercurrent however that, like the tantalisingly presented ageism in The Band Wagon, lends a real depth of bite to an otherwise grand old time. More madcap than melancholy, to be sure then, but it's that layer that ensures the picture resists dating/dulling the way a lesser musical of the period, like Stage Door Canteen, might.

So effortlessly is Singin In The Rain entwined with notions of the power/dominance of sound/performance, it's difficult to extract specific peaks amid a breathless flurry of such high points. Yes, the unerringly romantic reveal of Jean Hagan's utter humiliation forming the back drop and Gene Kelly/Debbie Reynolds reconciliation (after one of the most fleeting obstacles/break-ups in romantic comedy history?) is a high point. But the most sparkling, ingenious incident is the culmination of that initial, deeply unsuccessful experiment in sonic theatrics: the preview screening of "The Duelling Cavalier".

A sight gag worthy of The Marx Bothers -- and Comden and Green could certainly count themselves alongside the most literate and witty quipsters of the century -- plays out with simple precision timing by Donen the director and Kelly/Hagen as performers, as a mag-track hitches in the projector and his 'n' her words become entangled in the mouths operating with such furiously dramatic abandon onscreen. It's a startlingly sophisticated, almost post-modern sequence and, in its brief duration, infinitely more amusing than the anything whipped up by the execrable MST3K band or a curiosity like Hercules Returns.

Monday, 21 May 2007

The Good Old Naughty Days

"that's not even a pound a midget!"

I like to think that if Robert Stephens had still been around today he'd have made the sort of eccentrically inspired career choices that have enlivened the "Twilight"/"Troy"-strewn careers of Gene Hackman and Peter O'Toole in the guise of the impetuous Royal S. Tanenbaum and "Venus"' pervy old soak Maurice.

Not that I'm, contrarily, a great fan of either picture. But as dramatic/comedic lunacy, it's hard to beat the sight of either mischievous malcontent engaged in full-bore indelicacy.

The rattling off of a wickedly barbed quip seems to be an art lost amid today's sit-com saturated goofery. Whether it's much loved Raymond's bulbous-eyed savant act or Chandler Bing's weary contempt, it's ultimately a fairly sober brand of safe chuckles, mannered ticks and Pavlovian catch phrases.

Allow me a brief trip in to a more cine-illiterate past, one where I convinced myself that crashing through "Casablanca" and "Cinema Paradiso" in one sitting made me a casually hip nemesis to Barry Norman's pompous, blockbuster-shy critical faculties (more on these disastrous times as this blog goes on I suspect):

I remember vividly my first encounter with a non-costumed Peter O'Toole in Richard Benjamin's terrific "My Favourite Year". I say 'non-costumed' because, up until that time, O'Toole was, like a number of thesping greats, a fixture in the kind of romp I associated with quiet Sunday afternoons and subduded bank holidays: Charlton Heston's biblical butchness; John Mills' bewhiskered old boy status; and O'Toole's steely mug in "Lawrence..." (although, shockingly, I didn't see that until much -- much -- later, either) and "The Last Emperor". Of course, in "My Favourite Year" he was taking off part that very era of persona, the aging, swash-buckling bounder with whom time and the rigours of the bottle have well and truly caught up. I wouldn't for one moment suspect that the part was the least bit ethically troubling for O'Toole. But being so young -- a modest 16 at the time, 1992 -- and as far through my cinematic education as a second or third Welles, a single Ford, maybe three Kubricks and a handful of Hitchcock would allow, I hadn't the context within which to place such arch characterisation.

I'd seen enough Neil Simon and Mel Brooks to know the broad stokes of the 1950s Benjamin's picture was lampooning. But I hadn't so much heard a single note of Erich Wolfgang Korngold, let alone seen Eroll Flynn sliding down any pirate's rope or exhibiting rapier wit alongside his rapier. O'Toole's Alan Swann was, to me, a symbol of a black and white desert I had yet to lose myself in.

To say I was unexpectedly elated when I heard the following exchange:

[Having wandered into the wrong restroom, actor Alan Swann is greeted with the indignant cry] Lil:"This is for ladies only!"

Swann [rumaging in his fly]: "So is this madam, but every now and then I have to run a little water through it."

is an under-statement.

In a year where "Encino Man", "HouseSitter", "Kuffs" and "Mo Money" were rocking the joint with strained slapstick, it fell to something as incongruous as Peter Jackson's "Brain Dead" to provide a smattering of sophisticated (albeit low brow) wit. And I had discovered a small slice of undiscovered country. These old guys were hilarious. So what if this was a pastiche of an era, rather than a relic of the era itself. Wit was more than simply 'Bohemian Rhapsody' head-banged in the back of a station wagon through Aurora, Il (and certainly more than 'Carry On Camping', though I'd kind of figured that bit out for myself, thankfully)

In a very roundabout way, this brings me to the vertically challeneged quote above, uttered in a fit of sarcastic indignation by Robert Stephens at the start of Billy Wilder's "The Private Life Of Sherlock Holmes", with which I had my first wonderful encounter this weekend.

I like to think that if Robert Stephens had still been around today he'd have made the sort of eccentrically inspired career choices that have enlivened the "Twilight"/"Troy"-strewn careers of Gene Hackman and Peter O'Toole in the guise of the impetuous Royal S. Tanenbaum and "Venus"' pervy old soak Maurice.

Not that I'm, contrarily, a great fan of either picture. But as dramatic/comedic lunacy, it's hard to beat the sight of either mischievous malcontent engaged in full-bore indelicacy.

The rattling off of a wickedly barbed quip seems to be an art lost amid today's sit-com saturated goofery. Whether it's much loved Raymond's bulbous-eyed savant act or Chandler Bing's weary contempt, it's ultimately a fairly sober brand of safe chuckles, mannered ticks and Pavlovian catch phrases.

Allow me a brief trip in to a more cine-illiterate past, one where I convinced myself that crashing through "Casablanca" and "Cinema Paradiso" in one sitting made me a casually hip nemesis to Barry Norman's pompous, blockbuster-shy critical faculties (more on these disastrous times as this blog goes on I suspect):

I remember vividly my first encounter with a non-costumed Peter O'Toole in Richard Benjamin's terrific "My Favourite Year". I say 'non-costumed' because, up until that time, O'Toole was, like a number of thesping greats, a fixture in the kind of romp I associated with quiet Sunday afternoons and subduded bank holidays: Charlton Heston's biblical butchness; John Mills' bewhiskered old boy status; and O'Toole's steely mug in "Lawrence..." (although, shockingly, I didn't see that until much -- much -- later, either) and "The Last Emperor". Of course, in "My Favourite Year" he was taking off part that very era of persona, the aging, swash-buckling bounder with whom time and the rigours of the bottle have well and truly caught up. I wouldn't for one moment suspect that the part was the least bit ethically troubling for O'Toole. But being so young -- a modest 16 at the time, 1992 -- and as far through my cinematic education as a second or third Welles, a single Ford, maybe three Kubricks and a handful of Hitchcock would allow, I hadn't the context within which to place such arch characterisation.

I'd seen enough Neil Simon and Mel Brooks to know the broad stokes of the 1950s Benjamin's picture was lampooning. But I hadn't so much heard a single note of Erich Wolfgang Korngold, let alone seen Eroll Flynn sliding down any pirate's rope or exhibiting rapier wit alongside his rapier. O'Toole's Alan Swann was, to me, a symbol of a black and white desert I had yet to lose myself in.

To say I was unexpectedly elated when I heard the following exchange:

[Having wandered into the wrong restroom, actor Alan Swann is greeted with the indignant cry] Lil:"This is for ladies only!"

Swann [rumaging in his fly]: "So is this madam, but every now and then I have to run a little water through it."

is an under-statement.

In a year where "Encino Man", "HouseSitter", "Kuffs" and "Mo Money" were rocking the joint with strained slapstick, it fell to something as incongruous as Peter Jackson's "Brain Dead" to provide a smattering of sophisticated (albeit low brow) wit. And I had discovered a small slice of undiscovered country. These old guys were hilarious. So what if this was a pastiche of an era, rather than a relic of the era itself. Wit was more than simply 'Bohemian Rhapsody' head-banged in the back of a station wagon through Aurora, Il (and certainly more than 'Carry On Camping', though I'd kind of figured that bit out for myself, thankfully)

In a very roundabout way, this brings me to the vertically challeneged quote above, uttered in a fit of sarcastic indignation by Robert Stephens at the start of Billy Wilder's "The Private Life Of Sherlock Holmes", with which I had my first wonderful encounter this weekend.

And here it is, at last: a point !

Watching its jaunty couple of hours reaffirmed the simple pleasure of what it is to be able disover something so precisely and accutely great for yourself for the first time, even after thousands of reels of film have passed before your eyes.

Simple pleasures, most often given to us by discoveries fr om(or long overdue acquiantences with) cinema's past.

By that I don't means it's perfect. Far from it. It's a winsome piece of, well, whimsy. Or at least in Wilder's insouciant, sardonic style, perhaps he'd like you to believe that. It's not a story of great importance, of epic scope. It's intimate, of course, which is given away by the exact nature of the title, for those eagle eyed viewers who take note of such things (you'd be surprised how many/few this would apply to nowadays -- it seems as though "xXx" is about as droll as it gets these days with as unassumingly adroit titles as "A History Of Violence" few and far between). It spans weeks and miles in search of a solution to a particularly tricky mystery. But ultimately, the story concerns itself with nothing so much as why that solution is so rabidly, incisivey sought to the exclusion of all else in his life by the world's greatest consultant detective.

It's a humane and often hysterically funny piece of business. Like some kind of Garrison Keilor shaggy dog tale, we get submarines, monks, parasoles, ripping-yarn-loving monarchs, horny prima donnas and the aforementioned (missing) midgets schlepping us over much of the British countryside to little grand reveal of mystery and much ripe divulging of true character.

Reading Thom Taylor's book on the late-90s spec script market, "The Big Deal", into work today, it drove it further home. Written at a time when the sweat and musk of the spec script boom was still discernable on Hollywood's dirty bed linen, the book's mesage is clear: it's still all about the money. And that was nearly ten years ago.

How could Wilder's picture, something so capricious, frustrating, sublime, unruly, indulgent, literate and self-deprecating as to make its own director question the type of picture he'd made, have a home in today's maddenly immediate film industry?

How could as wicked a talent Robert Stephens, so fucking perfectly erudite as Holmes here, be allowed to work such flagrant and flamboyant weirdness into a star part today?

There's a short and obvious answer.

Johnny Depp manages to plumb comparative depths, but it beocomes, necessarily, a self-conscious facade in "Pirates Of The Caribbean". When he does it straight and niche, we get "From Hell". Or "The Libertine". From hell.

It's in moments like this weekend where I realise why I love pictures -- an how frustarting it is to work within an industry that will never be like this again. It's why looking back is so vital. There's always something to learn, some piece of the medium's history to uncover for yourself (no matter how in plain sight it has been all these years) . And when you discover such an exchange as this:

HOLMES

My dear friend -- as well as my dear doctor -- I only resort to narcotics when I am suffering from acute boredom -- when there are no interesting cases to engage my mind.

Watching its jaunty couple of hours reaffirmed the simple pleasure of what it is to be able disover something so precisely and accutely great for yourself for the first time, even after thousands of reels of film have passed before your eyes.

Simple pleasures, most often given to us by discoveries fr om(or long overdue acquiantences with) cinema's past.

By that I don't means it's perfect. Far from it. It's a winsome piece of, well, whimsy. Or at least in Wilder's insouciant, sardonic style, perhaps he'd like you to believe that. It's not a story of great importance, of epic scope. It's intimate, of course, which is given away by the exact nature of the title, for those eagle eyed viewers who take note of such things (you'd be surprised how many/few this would apply to nowadays -- it seems as though "xXx" is about as droll as it gets these days with as unassumingly adroit titles as "A History Of Violence" few and far between). It spans weeks and miles in search of a solution to a particularly tricky mystery. But ultimately, the story concerns itself with nothing so much as why that solution is so rabidly, incisivey sought to the exclusion of all else in his life by the world's greatest consultant detective.

It's a humane and often hysterically funny piece of business. Like some kind of Garrison Keilor shaggy dog tale, we get submarines, monks, parasoles, ripping-yarn-loving monarchs, horny prima donnas and the aforementioned (missing) midgets schlepping us over much of the British countryside to little grand reveal of mystery and much ripe divulging of true character.

Reading Thom Taylor's book on the late-90s spec script market, "The Big Deal", into work today, it drove it further home. Written at a time when the sweat and musk of the spec script boom was still discernable on Hollywood's dirty bed linen, the book's mesage is clear: it's still all about the money. And that was nearly ten years ago.

How could Wilder's picture, something so capricious, frustrating, sublime, unruly, indulgent, literate and self-deprecating as to make its own director question the type of picture he'd made, have a home in today's maddenly immediate film industry?

How could as wicked a talent Robert Stephens, so fucking perfectly erudite as Holmes here, be allowed to work such flagrant and flamboyant weirdness into a star part today?

There's a short and obvious answer.

Johnny Depp manages to plumb comparative depths, but it beocomes, necessarily, a self-conscious facade in "Pirates Of The Caribbean". When he does it straight and niche, we get "From Hell". Or "The Libertine". From hell.

It's in moments like this weekend where I realise why I love pictures -- an how frustarting it is to work within an industry that will never be like this again. It's why looking back is so vital. There's always something to learn, some piece of the medium's history to uncover for yourself (no matter how in plain sight it has been all these years) . And when you discover such an exchange as this:

HOLMES

My dear friend -- as well as my dear doctor -- I only resort to narcotics when I am suffering from acute boredom -- when there are no interesting cases to engage my mind.

(holding out one of the open letters)

Look at this -- an urgent appeal to find six missing midgets.

He tosses the letter down is disgust.

WATSON

Did you say midgets?

He picks up the letter.

HOLMES

Six of them -- the Tumbling Piccolos -- an acrobatic act with some circus.

WATSON

Disappeared between London and Bristol... Don't you find that intriguing?

HOLMES

Extremely so. You see, they are not only midgets -- but also anarchists.

WATSON

Anarchists?

HOLMES

(nodding)

By now they have been smuggled to Vienna, dressed as little girls in burgundy pinafores. They are to greet the Czar of all the Russias when he arrives at the railway station. They will be carrying bouquets of flowers, concealed in each bouquet will be a bomb with a lit fuse.

WATSON

You really think so?

HOLMES

Not at all. The circus owner offers me five pounds for my services -- that's not even a pound a midget.

it's always something pretty special.

it's always something pretty special.

You wonder why anyone would want it any different. but of course it must be. We just don't have to like it all that much.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)